At the Library of Congress, a mix tape for the ages

Published 9:18 am Wednesday, March 25, 2015

As announced early Wednesday, the annual list of sound recordings selected by the Library of Congress for inclusion in its National Recording Registry reads like the world’s most eclectic mix tape.

Just like its cousin, the National Film Registry, whose most recent additions ranged from obscure early silent films to “The Big Lebowski,” the 25 sound recordings just added to the registry run the gamut, from a turn-of-the-20th-century collection of over 600 wax cylinders featuring homemade recordings to the Doors’ 1967 debut to Radiohead’s 1997 masterpiece “OK Computer.”

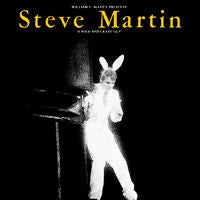

On the spoken-word side, additions include a recording of Arthur Godfrey’s emotional radio coverage of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s funeral (which took place 70 years ago next month) and a 1953 reading of the epic Civil War poem “John Brown’s Body” featuring actor Tyrone Power and others. Comic Steve Martin, honored for his 1978 album “A Wild and Crazy Guy,” joins such comedy honorees as Abbott and Costello (“Who’s on First?”) and the Firesign Theater (“Don’t Crush That Dwarf, Hand Me the Pliers”). Even goofier? The novelty song “Rubber Duckie” — part of the album “Sesame Street: All-Time Platinum Favorites” — also made the cut.

That’s as it should be, says Mickey Hart, former Grateful Dead drummer and tireless evangelist for sonic diversity, who serves on the National Recording Preservation Board and was instrumental in its formation. Created by an act of Congress in 2000, the NRPB makes annual recommendations of recordings, chosen for their cultural, artistic and historical significance, to Librarian of Congress James Billington, partly using nominations solicited from the public. Nominated recordings must be at least 10 years old.

Though often described as a world music expert, Hart bristles at that misnomer. “There’s no such thing as ‘world music,’ ” says Hart, who chatted by phone from his California studio. “If you’re in the Philippines, back-porch music from the Adirondacks is world music. The Doors are world music, if you’re from India.”

Describing those two words as a symptom of cultural arrogance, Hart says he’s particularly delighted by one item on this year’s list: a collection of 101 wax cylinders recorded at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, and featuring music from Fiji to Vancouver Island. “Indigenous music, that’s my baby,” says Hart, who traces his love of the genre to his discovery, at age 6, of a disc of Pygmy music tucked alongside a Duke Ellington album that his mother brought home.

The 71-year-old musician, whose practice these days consists of both his own compositions and the digital transcription of “endangered” music stored on such unstable media as wax cylinders, knows firsthand how fragile those old artifacts can be. “I’ve watched some of these things disintegrate in front of my eyes, as I’m recording,” he says, alluding to the “gremlins” that eat away at old media by the second.

“I’ve seen a recording give its life, man, on the last play.”

When it comes to the preservation of what he calls the “sounds of our civilization,” Hart practices what he preaches. The Dead, he says, long ago realized the value of recorded music, not just the tracks laid down in the studio, but the bootlegs and “board tapes” — recordings made by the band’s sound people — from live concerts. “We treat this stuff like gems,” he says, citing the climate-controlled vault in Los Angeles where the Dead’s musical archive is in the care of a dedicated archivist.

But preserving recordings is pointless, Hart says, if people can’t hear the stuff. He points out that the Grateful Dead were famous — well before the age of digital file-sharing — for allowing their legions of “tapers” to make, and share, recordings of the band’s performances.

That’s why, when asked what he would like to see added to the registry next year, Hart chooses not to name names. “I’d just like to see more access to it,” he says, praising the library for uploading sound clips from the registry’s collection, now at 425 recordings.

“If you just collect s—,” Hart says, “it don’t mean anything.”

– – – –

Recordings selected for the 2014 National Recording Registry, in chronological order

Vernacular Wax Cylinder Recordings at University of California at Santa Barbara

Library (c. 1890-1910).

The Benjamin Ives Gilman Collection, recorded at the 1893 World’s Columbian

Exposition at Chicago (1893).

“The Boys of the Lough” and “The Humours of Ennistymon,” Michael Coleman (1922).

“Black Snake Moan”and “Match Box Blues,” Blind Lemon Jefferson (1928).

“Sorry, Wrong Number” (episode of “Suspense” radio series) (May 25, 1943).

“Ac-Cent-Tchu-Ate the Positive,” Johnny Mercer (1944).

Radio Coverage of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Funeral, Arthur Godfrey, et al. (April 14, 1945).

“Kiss Me, Kate” original cast album, (1959).

“John Brown’s Body” (album), Tyrone Power, Judith Anderson and Raymond Massey; directed by Charles Laughton (1953).

“My Funny Valentine,” Gerry Mulligan Quartet featuring Chet Baker

(1953).

“Sixteen Tons,” Tennessee Ernie Ford (1955).

“Mary Don’t You Weep,” Swan Silvertones (1959).

“Joan Baez” (album), Joan Baez (1960).

“Stand by Me,” Ben E. King (1961).

“New Orleans’ Sweet Emma Barrett and her Preservation Hall Jazz Band” (album), Sweet Emma and her Preservation Hall Jazz Band (1964).

“You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin’,” Righteous Brothers (1964).

“The Doors” (album), Doors (1967).

“Stand!,” Sly and the Family Stone (1969).

“Lincoln Mayorga and Distinguished Colleagues” (album), Lincoln Mayorga (1968).

“A Wild and Crazy Guy” (album), Steve Martin (1978).

“Sesame Street: All-Time Platinum Favorites” (album), various artists (1995).

“OK Computer” (album), Radiohead (1997).

“Songs of the Old Regular Baptists,” various artists (1997).

“The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill” (album), Lauryn Hill (1998).

“Fanfares for the Uncommon Woman” (album), Colorado Symphony Orchestra, Marin Alsop, conductor; Joan Tower, composer (1999).