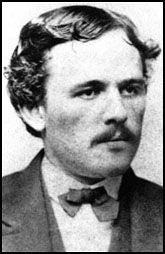

Louis Weichmann: An Indiana town’s connection to the Lincoln assassination

Published 6:30 pm Wednesday, April 15, 2015

In 1865, Louis Weichmann was a resident of the Surratt boarding house in Washington, D.C., where John Wilkes Booth and other conspirators plotted to kill President Abraham Lincoln, who died 150 years ago Wednesday.

After Booth fatally shot Lincoln during a performance at Ford’s Theater on April 14, 1865, Weichmann and other residents of the boarding house were held by authorities for questioning. Weichmann provided key testimony for the prosecution of the conspirators, including boarding house matron Mary Surratt, who was eventually convicted and hanged.

Weichmann later moved to Anderson, Indiana, where he had family. He died there in 1902 at his sister’s home but has since become a part of the Indiana town’s history.

—-

He was a teacher, a government clerk, a seminarian, a witness and the owner of a local business.

Some people thought he was handsome, charming and honest as sunshine. Others thought he was smarmy, a craven coward and liar.

Although Louis Weichmann has been dead for 113 years, people are still sharply divided over who he was and what he did — and why.

Louis Weichmann — or Lewis or Aloyius Wiechmann — was born in Baltimore to German immigrants in 1842. He spent his childhood in Washington, D.C., and Philadelphia, graduating from public school there. He began to study for the priesthood, but left the seminary shortly after the Civil War began and was a teacher for a short time before getting a job with the Commissary General of Prisoners in Washington, D.C.

In Washington, Weichmann boarded at the home of Mary Surratt, the mother of a fellow seminarian named John Surratt, who had also left the seminary and was a postmaster. John Surratt was also a courier for the Confederate Army.

Meeting John Wilkes Booth

At Mary Surratt’s home, Weichmann met John Wilkes Booth and several other men who were involved with Booth in schemes to kidnap or assassinate Abraham Lincoln and other government officials.

Weichmann knew the participants, but was not invited to join the plot, probably because John Surratt considered him an abject coward and he was a miserable horseman and pistol shot. Most likely, Mary Surratt’s involvement was minimal as well.

After Booth’s assassination of Lincoln, the residents of Surratt’s boarding house, who were known associates of Booth, were all arrested. Weichmann began, at an early stage, helping the government make its case against the conspirators, especially his former landlady.

Weichmann was one of the government’s star witnesses before the Military Commission that tried the Lincoln conspirators and his was the crucial testimony that convicted Mary Surratt.

His testimony impressed many people, among them General Lew Wallace, as being of impeccable honesty. Others, including men he had worked with, were inclined to regard Weichmann as a smarmy coward who was not to be trusted. John Surratt, who had escaped to Europe and was prosecuted for his part in the conspiracy but not convicted, claimed in later years that Weichmann was coerced by government officials who put a noose around his neck, threw the rope over a beam, lifted him off the floor and threatened to hang him with the conspirators if he didn’t testify.

After the trial, Weichmann got a job with the U. S. Customs Service in Philadelphia, which he kept through several safe Republican administrations, but the 1885 election of a Democrat found him jobless.

Landing in Anderson

Weichmann had family in Anderson, northeast of Indianapolis. His brother was a priest at St. Mary’s and two of his sisters lived there as well, so he moved to be near them.

His business and linguistic skills brought him a job teaching shorthand at a local business school and when it closed he started his own, where he was a well-regarded teacher.

He was not, however, the most popular resident of Anderson, and his school was small. Many people were outraged that his testimony had sent a woman to the gallows and were sure that he lied. He did have the support of his family, who became his staunch defenders and made themselves obnoxious to their neighbors.

Weichmann himself was nervous man. He feared reprisals for his testimony from the Surratts and developed a variety of peculiar habits.

He would never, according to his students, stand with his back to the door. He rarely left home after dark and never did so alone. He would never sit between a lamp and a window and was rumored to carry a derringer. He also had a strong desire to justify himself and wrote a book giving his account of the trial. Although it was not published in his lifetime, he gave it to at least one of his students to read and spoke of it often.

Weichmann died in June 1902 at his sister’s home on West Eighth Street in Anderson. Although he had not been a practicing Catholic since the trial in 1865, the local parish priest was called for.

Also on his deathbed, he wrote a statement in which he swore that his testimony at the trial had been the truth and nothing but the truth. Despite this statement, there is good reason for believing that Weichmann’s testimony was unreliable. Statements made by him to an associate shortly after the trial and to one of his students in Anderson in 1898 make it fairly clear that he was coerced by the government to lie and that Mary Surratt was innocent.

Louis Weichmann remains as controversial in death as he was in life.

His book remained in the hands of his niece until 1972. It was edited and published as “A TRUE HISTORY OF THE ASSASSINATION OF ABRAHAM LINCOLN AND THE CONSPIRACY OF 1865” in 1975.

The Anderson Public Library has a copy in the Indiana Room.

Researchers, both for and against him, still write to the library asking about his years in Anderson and his life there, an ironic tribute to a man who probably came to Anderson and to forget and be forgotten.

Oljace works at the Anderson, Indiana Public Library. The Anderson Herald Bulletin contributed to this report.